Album Liner Notes

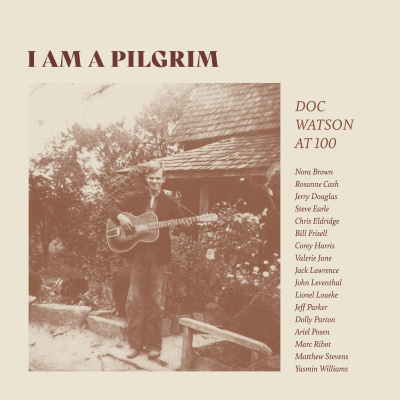

I Am A Pilgrim: Doc Watson At 100

Release date: April 28, 2023

Label: FLi Records/Budde Music

I Am a Pilgrim: Doc Watson at 100

When Arthel “Doc” Watson was born – on March 3, 1923 – radio and sound recordings had not yet reached his rural corner of western North Carolina. Musical styles in one valley of the Blue Ridge Mountains differed from those in the next and differed quite a bit from areas farther away. People didn’t travel far, and their music tended to stay home, as well. Doc knew his small crossroads of Deep Gap by heart; it had been homesteaded by an ancestor in the 19th century. Even blind, he could walk the pathways by himself, confidently navigating the region’s contours. “If my dad hadn’t bought my uncle’s car,” he told me once, “I don’t know when I’d ever have got to town.” By which he meant Boone, 17 miles up the road.

By the time of his death – on May 29, 2012 – Doc had brought his music not only to the far corners of America and many parts of Europe, but also to Japan, India and Africa. The songs that he had absorbed and transformed had touched the lives of millions. And he had influenced a host of important musicians, a number of whom have interpreted his songs for this tribute album.

Doc’s own influences came first from local musicians and later, when his father brought home a record player, from recordings by the likes of Jimmie Rodgers, Mississippi John Hurt and the Delmore Brothers. When the family acquired a radio, they spent Saturday nights listening to the Grand Ole Opry from far-away Nashville.

In his teenage years, young Doc Watson carried his Stella guitar to play with his neighbor Gaither Carlton, who had learned his fiddle tunes and technique during those days before records and radio. This gave Doc a direct line to early mountain music. He learned that lesson well. And he also learned to pay attention to Carlton’s daughter Rosa Lee, who became his wife of 66 years. “Shady Grove,” explored here by Jerry Douglas, was their courting song, the tune that won her heart. Their son Merle became his father’s musical partner, and their daughter Nancy became the family’s essential archivist.

By the time that folklorist Ralph Rinzler met him, in the early 1960s, Doc was playing in Jack Williams’s dance band. Williams was a big personality who once regaled me with tales of the band’s early adventures, including a rather turbulent moment featuring a woman and a washing machine. His band played a lot of fiddle tunes that Doc, a more studious and circumspect member, was already picking on guitar. That innovation would influence generations of players, including Jack Lawrence, who shows here what he learned as Doc’s second guitarist over the last decades of the master’s career. Rinzler’s collecting trip was initially focused on banjoist Tom Ashley, who brought Doc as his accompanist. Instantly recognizing the guitarist’s special talent, Rinzler told Doc he could probably have a career in the folk music revival. But first he had to jettison that electric Les Paul and find himself an acoustic guitar. So Doc recorded his first solo album on the Martin D-18 that Jack plays here.

As he ventured out into the wider world of performance, including solo bus trips that started on Route 421 in Deep Gap and ended at the New York Port Authority Bus Terminal, Doc had an immediate impact on the burgeoning folk music scene. I recall his solo performance at Club 47 in 1963: here was an artist fully in command of his instrument, but also deeply connected to the music and its cultural ecosystem. When he would sing a song like “Am I Born to Die” or “Little Sadie” or “Will the Circle Be Unbroken,” revisited here by Nora Brown, Chris Eldridge and Ariel Posen respectively, it was immediately clear that these songs had not been “learned” in the way that those of us just discovering the music studied them. To Doc the songs were almost innate, absorbed since infancy. We outsiders were asking to be let in to a rich and nurturing musical environment. Doc was not only already in that world; he was also of it.

Earlier that year, Doc performed at the Newport Folk Festival. He came with others, including Tom Ashley, the musician whom Ralph Rinzler was initially seeking, and family members: a couple of brothers, his wife Rosa Lee, even his mother Annie. Rosa Lee’s father Gaither Carlton played those old fiddle tunes. It was almost as if that ecosystem had been transported from Watauga County to the mansions and tennis courts of Newport, Rhode Island, summer home of the country’s financial elite. Doc shared a workshop with Bob Dylan, who would observe “the fellow can play the guitar with such ability...just like water running.”

As Doc gradually grew more comfortable hanging out in big cities with college kids – one story has him at Rinzler’s New York apartment during the blackout of 1965, where, as a blind man, he alone was able to lead people downstairs to the street – he began to pick up influences, as well as to provide them. He met and learned songs from writers like Tom Paxton. Years later Dolly Parton would duet with Doc on Paxton’s “The Last Thing on My Mind,” which she fondly recalls here in her own rendition. And Doc began composing his own tunes, like “Doc’s Guitar,” interpreted here by Yasmin Williams.

In 1964 Ralph Rinzler recommended that our company – Folkore Productions, aka FLi Artists -- represent Doc. We’ve been at it ever since. Early on, Manny Greenhill, my dad and the company’s founder, would go to booking conferences and try to convince arts presenters that traditional music was art, on a par with classical music and dance. For some reason, that view gained traction in northern college towns earlier than at home in the south. We used to joke that Doc couldn’t get arrested in North Carolina. But that eventually changed, and in 1986 he and Merle received the North Carolina Award in the Fine Arts. I recall their discussion about whether to wear tuxedos to the event. Doc was initially opposed. “Let Doc be Doc,” he grumbled. Merle, though not at all eager to dress so fancy, felt that they should observe protocol and do it anyway. Merle prevailed and eventually the Watson men outfitted themselves in the strange garments. The tuxedos then went into some closet until Merle’s sudden and tragic death from a tractor accident. When we pallbearers carried his coffin out of the church, Merle was dressed as if for that awards ceremony. (Decades later, when it was Doc’s turn, he entered eternity dressed in a western shirt, as if ready to sit and pick a bit.)

Merle’s death shook Doc to his core. He stopped performing for a spell, including turning down a featured spot on Saturday Night Live. Then one evening, as Rosa Lee was washing the dishes, she started singing to herself. “What’s that, honey?” Doc asked. “Oh just something...” That something became the chilling “Your Lone Journey,” a Watson original that has been covered by the like of Alison Krauss and Robert Plant on their Grammy-winning album and is here given a deep instrumental reading by Bill Frisell.

Doc eventually returned to concert and festival stages, albeit on a less intense schedule. When Wilkes Community College began to present MerleFest, honoring his lost beloved son, Doc enjoyed picking with a variety of musicians, from people like Earl Scruggs who had influenced him, to an array of those whom he had influenced, like Steve Martin.

At every performance he would always include “I Am a Pilgrim,” which Rosanne Cash lovingly renders here. The song became crucially important to him. Once, while several of us were accompanying him on stage, Doc sang it and then started weeping. I put down my guitar, left my chair and put my hands on his shoulders, trying to comfort him, to show him that he was loved and supported. When we talked about it later, Doc said he had been overcome by the image of his boy, a pilgrim, wandering alone.

Doc’s final performance was at MerleFest’s Sunday gospel set, a few weeks before he died. He had been clearly off his game that weekend, but somehow managed to summon the old Doc back for a final graceful guitar solo. Those last notes drifted up through the Blue Ridge pines that he had known all his life. Maybe they’re still out there somewhere, mingled with Gaither Carlton’s fiddle tunes and Merle’s slide guitar and a whole ancestral world of mountain sound.

When President Clinton presented the National Medal of Arts, he observed, “There may not be a serious, committed baby boomer alive who didn’t at some point in his or her youth try to spend a few minutes trying to learn to pick a guitar like Doc Watson.” Inspiration like that is what has led this group of committed artists to drop whatever else they were doing and to celebrate 100 years of Doc Watson.

-- Mitch Greenhill 2023 President of FLi Artists/Folklore Productions. Mitch is the author of Raised by Musical Mavericks: Recalling life lessons from Pete Seeger, Lightnin' Hopkins, Doc Watson, Rev. Gary Davis and others