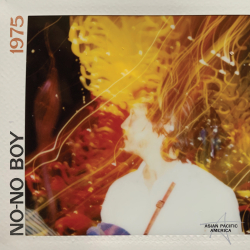

No-No Boy announces the release of 1975, Brown PhD dissertation-turned-album dissecting the Asian-American musical experience

Julian Saporiti's latest "act of revisionist subversion" (NPR) out April 2, 2021

Pre-order via Smithsonian Folkways HERE

Julian Saporiti, the musician and historian whose work under the name No-No Boy has been called "an act of revisionist subversion" by NPR, has announced the release of his second album, 1975, out April 2 on Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. The songs, which were recorded as part of Saporiti's Ph.D. dissertation at Brown University, use traditional American folk music sounds to question the concept of the genre, and who and what "counts" in traditionally American folk music. Production-wise, they are informed by Saporiti's desire to "put the sound back into history" via tapes of oral histories, field recordings, and the use of outmoded recording technology. The album's twelve songs are guided by Saporiti's desire to "rethink what we think of as authenticity for popular American music," as filtered through his perspective as a first-generation Vietnamese American who came of age in the folk, country, and indie rock scenes of Nashville.

Read more about No-No Boy's latest track, "Imperial Twist" at American Songwriter here: https://americansongwriter.com/premiere-no-no-boy-imperial-twist/

Listen to "Imperial Twist" here: https://open.spotify.com/album/57hOUJA2nXzFQTq6vOJ5nb?highlight=spotify:track:5RqX9DbOxlMFsJkJOejrEW

Pre-order the album here: https://folkways.si.edu/no-no-boy/1975

The project that would become No-No Boy began at the site of Heart Mountain War Relocation Center, a Japanese internment camp in Wyoming. There, Saporiti encountered a photo of an all-Japanese jazz band that had formed while its members were incarcerated by the U.S. government. Though he had studied jazz at Berklee School of Music, he had no framework for the possibility of Asian musicians playing jazz- much less under such dire circumstances. The discovery led him to investigate how Asian musicians confronted with the musical thrills- and imperial power- of American culture had adapted jazz, psychedelic rock, and country music to fit their own needs. The project had special resonance for him. "Even though I grew up in Nashville and grew up loving that music and literally in the industry," he says, "there was always something that didn't fit, because I look the way I do." No-No Boy became a way of "making space for myself as a younger musician," as he puts it.

Saporiti does this in part by expanding the vocabulary of American folk music to more accurately reflect the makeup and depth of experiences of people who live in this country. The instrumental palette on 1975 will be familiar to fans of Okkervil River, Pete Seeger, and The Avett Brothers; Saporiti sings in a clear, resonant baritone reminiscent of Jonathan Richman and Shearwater’s Jonathan Meiburg, and his devotion to what he calls "the Beatles school of melody writing" is buoyed by mandolins, acoustic guitars, and rich harmonies. But where recorded folk music has always been filled with Casey Joneses and Old Dan Tuckers, here we encounter Tomoki Ogata and George Igawa. These are not archetypes or characters, but actual human beings- the former a Japanese immigrant who died by suicide in the 1940s, the latter the "OG Nisei" who led the jazz band at Heart Mountain. By putting their lives into song, Saporiti implicitly makes the case that they deserve to be named, and to have their names sung into our shared history.

Still, Saporiti is a storyteller, not a polemicist. While political issues both cause and stem from everything that happens on 1975, Saporiti presents these songs as recollections of forgotten tragedies- some world-historical, some personal- without prescribing a reaction. "There are enough people lecturing, enough TED talks, enough dry academic articles," he says. This is an album of immersions, attempts to bridge the distance between stories being told and lives being experienced. The songs are anchored by field recordings Saporiti captured during his research: students clapping and stomping in the barracks of an internment camp, gravel footsteps in a Chinese cemetery in Oregon, knocking on wood at the Angel Island immigrant detention center off the coast of San Francisco. "You put that in your headphones, you mix it with reverb or vibrato, then you've taken yourself out of the present."

Elsewhere, Saporiti writes with touching grace about his mother, who emigrated from Saigon after her grandfather was assassinated in the Tet Offensive. He sings touchingly about the complexities of relating to his bà ngoai (his mom's mom) and navigating his identity as a Vietnamese American at a time "before the Banh Mi trucks were cool." In "Tell Hanoi I Love Her," his fascination with his heritage ("I named my Chrysler after Ho Chi Minh," he quips) butts up against a friend's "Bedazzled star-spangled t-shirt tiger mom." He contemplates the connections between South Vietnam and the American South and wonders at the way horrifying experiences can shape our view of the present, and our values. "Honouliuli" finds him distressingly cocooned in a distorted version of Hawai'i, the intense disorientation of the production mirroring the disassociation he felt while suffering a "panic attack in paradise."

1975 is filled with heavy stories, but whether Saporiti is singing about himself, hailing the Saigon psych band whose version of "Purple Haze" was interrupted by a bombing raid, or surveying the graveyard in a former concentration camp in Colorado, he approaches his songs with kindness and wisdom. At its heart, No-No Boy is "a project of uplift," he says. That sense of uplift is a direct product of how long he’s sat with these histories, and so many like them. "When you actually look into history, or when you actually look into your contemporary moment, it's a mess," he says. "But if you sit with that mess, and do some deep listening and meditate on it, you might learn from it. And that's what this record tries to do- just sit down for a second and listen. Not to my music so much, but to the past as best you can. When you listen, things have to calm down." This calm, quiet, and open territory is where No-No Boy makes his home.

About Smithsonian Folkways

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, the "National Museum of Sound," makes available close to 60,000 tracks in physical and digital format as the nonprofit record label of the Smithsonian, with a reach of 80 million people per year. A division of the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, the non-profit label is dedicated to supporting cultural diversity and increased understanding among people through the documentation, preservation, production and dissemination of sound. Its mission is the legacy of Moses Asch, who founded Folkways Records in 1948 to document "people's music" from around the world. For more information about Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, visit folkways.si.edu.

Follow Smithsonian Folkways:

Official website: folkways.si.edu

Facebook: facebook.com/smithsonianfolkwaysrecordings

Twitter: twitter.com/folkways

Instagram: instagram.com/smithsonianfolkways