Album Liner Notes

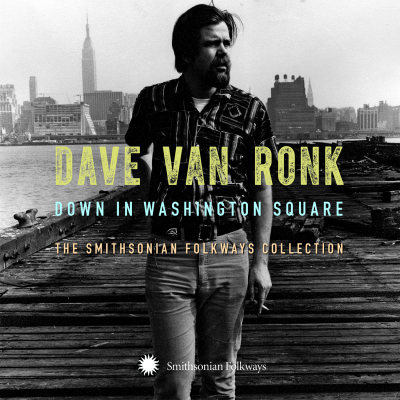

Down In Washington Square: The Smithsonian Folkways Collection

Release date: October 29, 2013

Label: Smithsonian Folkways

Down In Washington Square: The Smithsonian Folkways Collection

"Down In Washington Square"

Sunday when the clock strikes noon

Just drop whatever else you’re doin’

Motivate ’cross town and soon

You’re there

Bring your axe and wear your shades

It’s a proletarian masquerade

They’re jamming on the barricades

In Washington Square

Beatnik poets with conga drums

Uptown virgins and Bowery bums

Bluegrass picking and flamenco strums

We’ll all be singing “Tzena Tzena” when the wagon comes

If you bought that banjo yesterday

It doesn’t matter if you can’t play

Nobody else can anyway

Down in Washington Square

If your head is pounding and you’re still a little tight

From that vino cheapo that you drank last night

You can scream until you feel all right

It’s laissez faire

You can dance the hora, you can do a soft shoe

You can sing “Greensleeves” till your face turns blue

Believe me, there ain’t much you can’t do

In Washington Square

Wear your big hoop earrings and your leotard

’Cause we’re gonna rub elbows with the avant-garde

I’ve got some Panama Red and my Yipsel card

And we’ll do-see-do with the Riot Squad

Last night I had the strangest dream

Joe Hill was singing “Goodnight Irene”

O nobody knows the troubles I’ve seen

Down in Washington Square

—Dave Van Ronk

So, there you have it: the last song Dave ever wrote. Not that he planned it that way, but neat and appropriate, somehow, to end at the beginning. And despite his irreverent streak—which obviously remained healthy until the end—he was always grateful to have been in the right place at the right time, out there on the cutting edge in Greenwich Village in the late 1950s.

Dave loved to describe his first visit to the Village in about 1951, the object being to check out the music scene in the park. Apparently, he envisioned half-timbered Tudor cottages with thatched roofs, and was horrified to see a neighborhood that looked

to his 15-year-old self a lot like Brooklyn. He obviously got over his disappointment fairly quickly, because within a few years he was living in the Village, and he continued to make it his home for pretty much the rest of his life. And by about 1956, he was a regular in Washington Square Park—serving his “apprenticeship,” in a sense—developing a repertory of songs, guitar techniques, and performing skills that would carry him through a career that lasted more than forty years. And hanging out with an assortment of interesting and talented people, sowing the seeds of a number of lifelong, cherished friendships.

It all sounds so romantic and exotic, especially to those of us who weren’t there. And as much as I would love to be able to give a firsthand account of Dave’s first glimpse of Washington Square Park, it just isn’t an option. His final visit, though . . . that one I know all too well.

Fast forward to March 1, 2002. St. David’s Day. The day I had selected for gathering with a few close friends at a church just a few blocks north of Washington Square. We’d have a brief, informal ceremony—pretty improvisational, really—prior to placing Dave’s ashes in the columbarium. Then off to a more secular location for a less sedate send-off.

Accompanied by Dave’s longtime friend Sylvia—to whom I shall forever be grateful—I made my way to the funeral home on Bleecker Street, where I was handed a large, white shopping bag which contained a marble urn. As we walked north on MacDougal, Sylvia pointed out Dave’s first apartment in the neighborhood, and reminisced a bit about various long-gone clubs and hangouts. We cut into Washington Square Park. That marble urn was beginning to feel mighty heavy. We sat down on a bench in the middle of the park, not too far from the fountain. Didn’t say much. Just rested for five or ten minutes, then got up and headed toward the arch and up Fifth. Nothing elaborate: no brass band, no second line; but, thinking back on it, I’d have to say it was neat and appropriate. (Yes, Dave, we all benefit from a certain amount of . . . distance.) Just a quiet farewell in the place where it all began. A homecoming, in a way. A logical conclusion to Dave’s 50-year love affair with the Village.

These days I walk through the park on a fairly regular basis. And there is pretty much always music going on. The east and west transepts seem to attract small jazz combos, or the occasional lone horn player. There’s a pianist who wheels in his baby grand, taking advantage of the natural acoustics beneath the arch. And walking past the fountain still entails dodging innumerable folkies and bluegrassers, flailing away on guitars and banjos and mandolins while belting out all those songs you’d forgotten you ever knew. And I can picture Dave so clearly, rolling his eyes heavenward and muttering, Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose. I giggle to myself, and give his blessing to one and all. —Andrea Vuocolo

Dave van Ronk (1936–2002)

“I never really thought of myself as a ‘folksinger’ at all. Still don’t. What I did was combine traditional fingerpicking guitar with a repertory of old jazz tunes, many of which I’d been singing for years. These recordings from ’59 and ’61, I regard as a journeyman’s progress report” (Van Ronk, notes to SFW 40041). This quote shows Dave Van Ronk, as his usual self-deprecating self. Called the “Mayor of MacDougal Street,” Van Ronk was for decades a fixture in the Greenwich Village music scene. He was a raconteur who was extremely well read and always ready to provide a quick quip on a subject at hand. More important, although he never achieved pop icon status, Van Ronk was the “guru on the mountain,” teaching and advising many other musicians who went on to greater fame.

He was already an established figure in New York when a young Bob Dylan hit town in 1961. Dylan, who resided on Van Ronk’s couch for a while, would learn how to finger-pick the guitar from the master. Twenty years later, when a newer group of young songwriters were gathering in a local Greenwich Village club called The SpeakEasy to share their new compositions and hone their writing skills, Van Ronk was the “grand old man” on the scene and an obvious mentor. Writers such as Jack Hardy, Suzanne Vega, Christine Lavin, Frank Christian, and others would benefit from Van Ronk’s experience.

Dave Van Ronk was born in Brooklyn, New York, on June 30, 1936. He came from an Irish and Dutch background. He acquired a ukulele at 12 years old and a guitar a year later (Van Ronk, notes to SFW 40041), and then he learned the banjo. His initial love was jazz, singers like Bessie Smith, Billie Holiday, Jelly Roll Morton, and Louis Armstrong.

“Trad jazz” or traditional jazz is a style of jazz harkening back to the sound of the early jazz (pre-Swing) bands of the 1920s and ’30s. It underwent a revival in the 1940s and ’50s, in both the United States and England. Many of the later British rockers of the 1960s got their start in groups such as Chris Barber’s trad jazz band. Van Ronk was taken with this music and began to perform it on banjo, where he clanged away, “occasionally hitting the right chord, and tolerated by my confreres mainly because I didn’t mind doing vocals and I sang real loud” (notes to SFW 40041). His first guitar teacher was Jack Norton, who had been “an associate” of Bix Beiderbecke and jazz guitarist Eddie Lang. Norton taught Van Ronk how to really listen carefully to the music (Wald 1996, 60).

Van Ronk hung out a lot at places like the Jazz Record Center, acquiring old records from the 1920s and ’30s. From these records he began to learn about some of the great blues singers like King Solomon Hill, Blind Lemon Jefferson, and Furry Lewis (Kip Lornell, notes to SFW 40041). For a time he played with the Brute Force Jazz Band. Unfortunately, though, Van Ronk got involved with the trad jazz revival just as it was at its end. Musicians were having a hard time finding gigs and putting food on the table.

He met the great folksinger Odetta in 1957, and she encouraged him to perform folk songs in concert. He had also started to spend time at the jam sessions around the fountain in the middle of Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village. These had been going on since the 1940s, but by the time Van Ronk heard about them they were a big deal. On a given day one might find banjo player Roger Sprung, members of The New Lost City Ramblers (John Cohen, Mike Seeger, and Tom Paley), and even Pete Seeger, Jack Elliot, or Woody Guthrie there. He encountered guitarists like Paley, Dick Rosmini, and Fred Gerlach (a fine 12-string player influenced by Lead Belly). Some of the players were doing a style called finger-picking. Van Ronk remembered, “They were playing music cognate with early jazz, with a subtlety and directness that blew me away. The right thumb keeps time—not unlike the left hand in stride piano playing—while the index and middle fingers pick out melodies and harmonies.... [I]f you can do this you don’t need a band” (notes to SFW 40041). The sessions at the park provided a musical education to all who attended, and Van Ronk undoubtedly brought his own knowledge of jazz to the mix.

Trad jazz and folk music intersected in the jug band, a real do-it-yourself kind of music (skiffle music in England was like that too). Many of the later stars of folk music and even rock started out in jug bands (the Jim Kweskin Jug Band; Even Dozen Jug Band; Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions). It was only natural that Dave would enjoy this kind of music.

Van Ronk recorded jug band music for Sam Charters, a blues and jazz scholar who wrote the first book on country blues, The country blues, in 1959. On his travels, Charters recorded many artists, including Lightnin’ Hopkins and Gus Cannon. Van Ronk, Charters’ future wife Ann Danberg, Len Kunstadt, and Russell Glynn recorded an album of jug band music for the Lyrichord label as the Orange Blossom Jug Five. Later Van Ronk felt embarrassed by the recording quality of this album. He would record for Charters’ Gazell label towards the end of his life.

Another important influence on Dave during the 1950s was Harry’s Smith’s anthology of american folk Music. Released in 1952 by Folkways Records, the anthology featured reissues of 78s from Smith’s personal collection of folk, string band, Cajun, blues, and jug band music, dating from the period 1926–1934. It reintroduced the world to musicians like Mississippi John Hurt, Clarence Ashley, and Dock Boggs. Musicians who had been exposed to more polished folk performers—for example Burl Ives, Marais and Miranda, or Richard Dyer-Bennet—now got to hear the raw stuff. One of the early devotees was Van Ronk, who first heard the record in 1954.

During the “folk song revival” of the late 1950s and ’60s, a credit you were likely to see on collections of American folk songs by any of the folk song interpreters was “Edited by Kenneth S. Goldstein.” He produced and wrote liner notes, providing the historical background on the songs, for over a hundred albums for Folkways, Elektra, Riverside, Stinson, and other labels. He would later become a distinguished professor of folklore at the University of Pennsylvania. It was Kenny Goldstein who brought Dave Van Ronk to the attention of Folkways.

Folkways Records and Service Corporation was a record label run by Moses Asch and Marian Distler in New York. Asch used the term “Service Corporation” to argue that his label existed not only for profit but as an entity to provide important sounds to the public. Asch thought of the label as an encyclopedia of sound and produced 2,168 albums over an almost forty-year period. He released recordings of ethnic music, blues, jazz, children’s music, spoken word, and sounds, as well as folk music. Folkways was already an established folk label when the folk song revival came into full bloom, and Asch certainly published New York folksingers. He ran the label until 1986; in 1987 it was acquired by the Smithsonian Institution.

Goldstein produced the first Van Ronk Folkways album, ballads, blues and a spiritual (1959). It was a mix of Dave’s arrangements of folk tunes, jazz, and blues tunes. In October 1960, Van Ronk recorded a follow-up album, dave Van ronk sings. Both were later reissued by the Verve/Folkways label with different covers and titles. (Verve/Folkways was a licensing deal Asch had with MGM Records for a brief period in the 1960s.)

One unusual Van Ronk project from this period was an album of sea shanties recorded by Paul Clayton and the Foc’sle Singers, a group that consisted of Van Ronk, his singer friend Clayton, Bob Brill, and Roger Abrahams (also later a professor of folklore at Penn). The seeds of the project were planted at some boisterous afternoon sing-alongs accompanied by pitchers of beer at Art

D’Lugoff’s Village Gate. Eventually enough songs were worked up to make an album for Folkways (Van Ronk, notes to SFW 40041). In actuality, it is a very good set of sea shanties, well annotated by—who else—Kenneth Goldstein.

Van Ronk was only with Folkways for three years before moving on. He and Asch had an interesting relationship. They got along fine, but there was always the question of royalties. Some of Van Ronk’s stories about this are legend. He once enlisted the help of a lawyer acquaintance to write a letter to Asch on the lawyer’s letterhead. He got paid. He happened to encounter Asch a few days later, and Asch said, “Dave, you’re gettin’ smart.”

Van Ronk left Folkways in 1963, recording his album folksinger for Prestige, a New Jersey label. A collection of jazz tunes In the tradition followed in 1964, and then Inside dave Van ronk. He switched to Mercury for two albums, one with the Ragtime Jug Stompers. His 1968 album for Verve, dave Van ronk and the hudson dusters, was a major departure stylistically, heading as it did in the direction of psychedelic rock.

It included versions of “Alley Oop,” an early arrangement of Joni Mitchell’s “Clouds” (“Both Sides, Now”), and a rock version of “Dink’s Song” (disc 2, track 2). There were even 45 rpm singles from the album released for radio.

Dave also recorded a jug band version of Peter and the wolf, a collection of Bertolt Brecht–Kurt Weill songs with Frankie Armstrong, and two albums of jazz standards. In 1997, Smithsonian Folkways reissued the anthology of american folk Music to great fanfare. In collaboration with the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum and others, the Smithsonian presented two concerts at the Barns of Wolf Trap celebrating the anthology. We looked to feature traditional musicians representing the genres of music included on the set. In addition, we invited musicians who had been influenced by the anthology or the collection’s compiler, Harry Smith, such as John Sebastian, Peter Stampfel, The Fugs, The New Lost City Ramblers, and Dave Van Ronk. A compact disc collection came out of the concert with one Van Ronk performance, “Spike Driver Blues,” but here on down inwashington square is the rest of Van Ronk’s set for the first time.

His final concert in October 2001 for the Maryland-based Institute for Musical Traditions was recorded by David Eisner. After Dave’s death in 2002, his family and friends were anxious for the recording to be released. In 2004 Smithsonian Folkways published it as ...and the tin pan bended and the story ended. In 2005, Da Capo Press published Dave’s memoir (written with Elijah Wald), The Mayor of Macdougal street. A wonderful compact disc of the same name was also released, including outtakes and rarities from the years 1957 to 1969.

Looking back at Van Ronk’s music, one thing that set him apart was his unique arrangements of others’ songs. He was one of the first interpreters of Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell.

He considered the music as an accompaniment to his singing and brought many elements from jazz, blues, and even classical music into his arrangements of songs. Writer, biographer, and longtime Van Ronk guitar pupil Elijah Wald points out that his “definitive setting for Joni Mitchell’s ‘Urge for Going’ harkens back to Domenico Scarlatti, while his version of ‘Both Sides, Now’ (according to Van Ronk) is a ‘pared down version of the first two measures of the chorus of the Rolling Stones’ ‘Ruby Tuesday” (Wald 1996). His attention to detail in his arrangements created music that is a lovely complement to his vocals.

The last five tracks on disc 3 were made available for inclusion on this album by Dave’s widow, Andrea Vuocolo, and were recorded by Dave during the last few years of his life. The same songs appear as concert performances on the recording ...and the tin pan bended and the story ended.

In late 2013, the Coen Brothers will release a major motion picture loosely based on Dave Van Ronk’s memories of his life and times in the Village in the early 1960s. Hopefully, publicity for the man himself will follow, and many more music fans will discover the joy of Dave’s music.