Smithsonian Folkways RecordingsClient Information

8 June, 2023Print

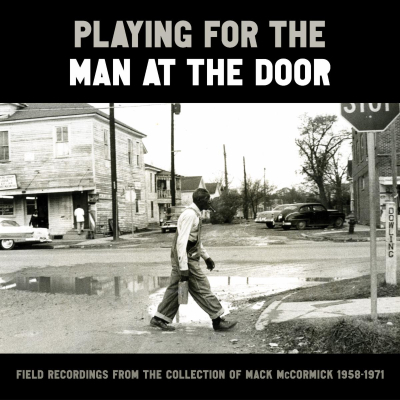

Playing for the Man at the Door: Field Recordings from the Collection of Mack McCormick, 1958 – 1971 out 8/4 on Smithsonian Folkways

Official sampler, featuring Mance Lipscomb, James Tisdom, Dudley Alexander and Washboard Band, The Spiritual Light Gospel Group, and George "Bongo Joe" Coleman, out today HERE

First-ever public release of music from McCormick collection made possible by last year's donation of McCormick archive to the Smithsonian

Robert “Mack” McCormick’s legend among music writers and fanatics comprised two main eras: The first was a manically prolific stretch from the late 1950s through the 1960s that saw him embark on intensive fieldwork, knocking on countless doors throughout a region he dubbed “Greater Texas” — which included his home city of Houston, East Texas, Western Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, and sections of Oklahoma and Arkansas — in order to record predominantly African American musicians performing the blues and other examples of Southern vernacular music. Then came a longer period that lasted until his death in 2015 where his largely-unreleased archive of hundreds of recordings amassed a fabled reputation. “Like John Lomax and his son Alan Lomax,” explains scholar Mark Puryear, “McCormick viewed the collection and preservation of African American and other ethnic groups’ folk traditions as central to understanding this country’s cultural and social values.” However, McCormick did little in the way of disseminating the invaluable musical histories he had documented, and because his archive of hundreds of recordings remained largely unreleased during his lifetime, it amassed an even more fabled reputation.

This year, the Smithsonian — as part of a yearlong slate of programming including the April 4 publication of McCormick’s unfinished Robert Johnson history, Biography of a Phantom, and a new exhibition of items from McCormick’s archive opening June 23 at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History — finally opens the vault.

On August 4, Smithsonian Folkways Recordings will release Playing for the Man at the Door: Field Recordings from the Collection of Mack McCormick, 1958 – 1971, a three-CD / six-LP box set of previously unheard field recordings from McCormick’s archive that includes a 128-page book of photographs from the collection and essays by leading blues scholars from the Smithsonian and beyond. Playing for the Man at the Door, produced and curated by Jeff Place of Smithsonian Folkways and John Troutman of the National Museum of American History, not only illuminates the music of an underexplored time and place in African American history, but prompts questions about the problematic racial dynamics and notions of ownership that fueled this white collector’s documentation of Black artists. “As McCormick sought to find the next commercially viable Huddie ‘Lead Belly’ Ledbetter or Mississippi John Hurt,” says John Troutman, curator of music at the National Museum of American History and co-producer of Playing for the Man at the Door, “what he found was far more sublime — a rich tapestry of voices by people who had entertained their families, neighbors and communities long before and long after folks like McCormick came knocking. Although many of the people featured in McCormick’s collection were little known beyond their intimate circles of family, friends, co-workers, fellow buskers, nightclub patrons, and church congregants, the musical traditions they nurtured and sustained, cultivated and innovated, will continue to nourish and prompt contemplation for all who hear their voices.”

For a first-listen, check out the official sampler, out today, which showcases the breadth and depth of the box set and the McCormick archive at large.

Featuring Mance Lipscomb, James Tisdom, Dudley Alexander and Washboard Band, The Spiritual Light Gospel Group, and George Coleman, get a sense for the diverse sounds (blues, gospel, everything in between) of the collection via the sampler HERE

While the collection does feature recordings of relatively well-known musicians like Lightnin’ Hopkins and Mance Lipscomb, many of the musicians cataloged by McCormick were not professionals in the modern music industry sense, but rather community musicians who provided entertainment in locales where their vernacular music, secular or religious, served as a welcome soundtrack. Playing for the Man at the Door includes recordings captured everywhere from hootenannies at Houston nightclubs to living rooms, and each performance features all the contours and textural detail of a great short story. George “Bongo Joe” Coleman gives his revolutionary campaign pitch to passing tourists in Galveston on “George Coleman for President, Nobody for Vice President,” while Billy Bizor expertly pitch-bends his harmonica during a performance of “Fox Chase” at his cousin Lightnin’ Hopkins’ 50th birthday show at Houston’s Alley Theater. There are spirituals (Hardy Gray’s unhurried but hopeful take on “Come and Go with Me to That Land”), country tunes (James Tisdom’s swinging, ad-lib-heavy “Salty Dog Rag”), zydeco bands (pioneers Dudley Alexander and Washboard Band’s swaggering “St. James Infirmary”), and rambling auctioneer calls, including a “Medicine Show Pitch” from bluesman Murl “Doc” Webster. There’s even the last-ever recording of a musician named Joe Patterson performing on the quills — an older African American music tradition centered on a wind instrument similar to panpipes that was constructed by bound reeds — captured from a hospital bed in a still-segregated psychiatric institution in Alabama.

|

|

|